Monthly Investment Commentary | May 2013

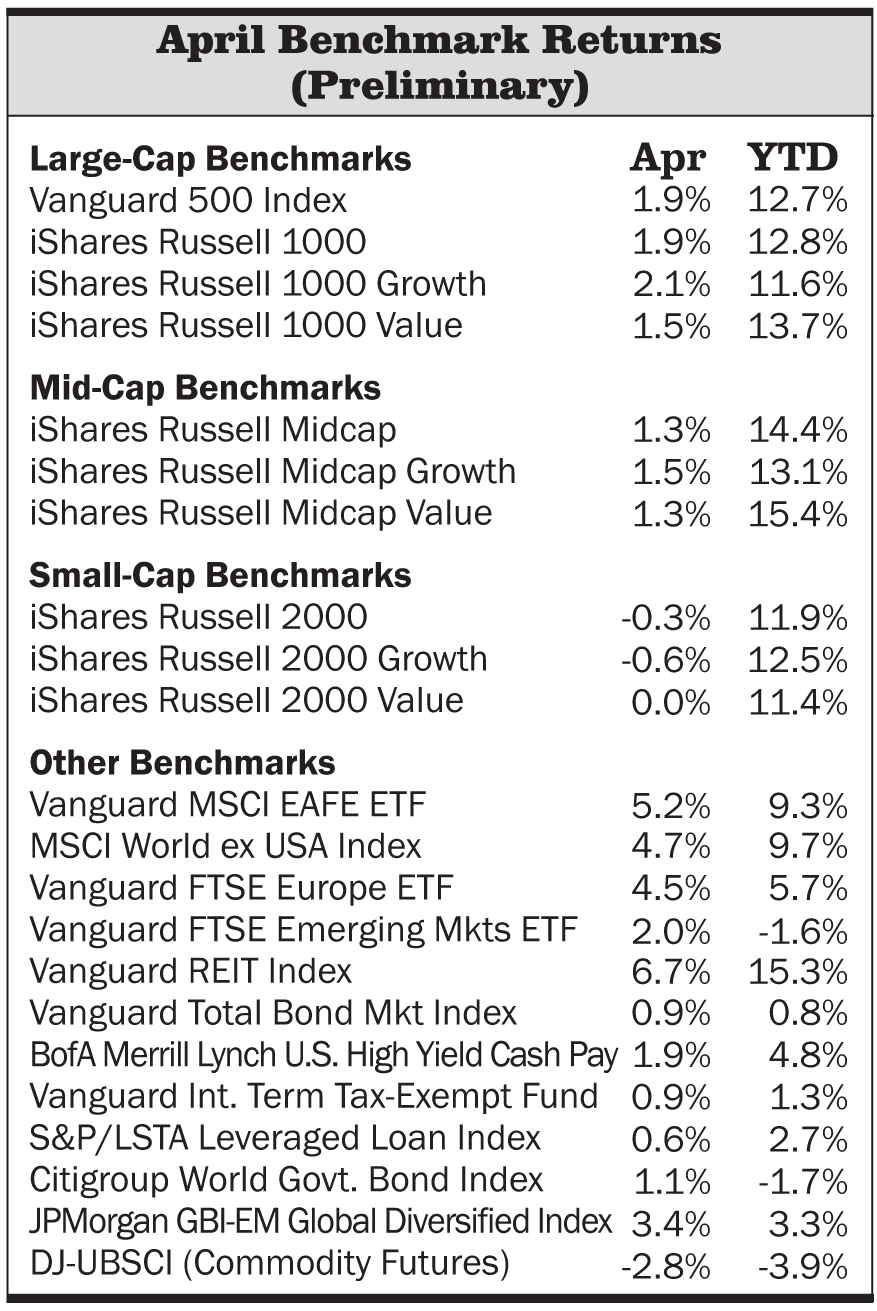

Stocks continued their positive streak in April despite a mixed bag of economic news, including some indications of slower global growth. In the United States, first-quarter GDP growth showed a significant uptick from the fourth quarter of 2012, but was lower than many forecasters expected. Reduced government spending—an effect of the sequester—was one negative for growth, as had been expected, though consumer spending was a stronger positive contributor than had been true in prior quarters, perhaps reflecting a “wealth effect” from gains in stocks and housing. It’s also the case that personal savings have dipped and income growth remains sluggish, both of which suggest consumer spending may not be sustainable in the face of still-high debt levels. Stocks fell during the first half of the month but then regained strength and the S&P 500 finished in record territory, rising 1.9%. Small-cap stocks did not fare as well and the Russell 2000 was slightly negative. (See performance table at right for complete benchmark returns.)

Turning abroad, foreign developed stocks outperformed U.S. stocks in April (reversing their standings in the first quarter) even as the economic recovery remained fragile. Despite grim economic statistics in many cases, yields have remained low in peripheral Europe, enabling countries to lower their debt service costs and more easily issue bonds. We continue to regard Europe as a risk factor, however, as there has been no real progress toward fiscal or banking union and the weak economic picture further complicates efforts to reduce debt. Among emerging markets, China’s economy showed some signs of short-term slowing, though GDP growth overall remains relatively strong. The MSCI EAFE rose 5.2% and emerging-markets stocks were up 2% in April.

In bond markets, investors continued to take on varying degrees of credit risk in pursuit of higher income. The Merrill Lynch High Yield index gained 1.9% and floating-rate loans rose 0.6%. At the same time, Treasurys rose slightly and yields declined. Our portfolios are underweight core bonds, and therefore Treasurys. However, we own a number of funds that selectively take on credit risk and these tended to outperform in April. Our exposure to emerging-markets local-currency bonds (which we fund with some of the proceeds of our equity underweight) was favorable as the U.S. dollar weakened slightly in April.

There has been no change in our investment views or portfolio positioning. We remain underweight stocks, particularly U.S. stocks based on our expectation of subpar five-year returns in all but our most optimistic scenario. Our overall stock allocation remains tilted toward emerging markets and, within our U.S. stock position specifically, we are underweight small caps in favor of large caps.

As stocks have continued to rise, without corresponding improvement in fundamentals in our view, their potential return is lower. This is particularly the case with U.S. stocks. Emerging-markets stocks remain quite a bit more attractive looking out over our five-year analysis horizon. In this month’s Q&A commentary, we discuss our process for determining when—or if—we would further reduce stocks and we review our thinking on how our portfolios might perform if the market declines significantly from here. We also discuss our outlook for the eurozone (as well as our recent exit from our European stock tactical allocation), and review our thinking on municipal bonds.

In your first quarter commentary, you mentioned you are getting closer to further reducing your stock exposure. Can you talk about the factors involved in this decision?

When deciding how much equity risk we should have at the portfolio level, we look at not only what returns we expect from U.S. equities, but also returns from other regions, such as Europe and emerging markets, and we do this across our four broad economic scenarios.

Looking at the full global equity opportunity set is even more critical now given the enhancements we have made to our portfolios over the past year or so. One, we significantly increased our weighting to foreign stocks in our strategic portfolio allocations in January 2012, largely stemming from an increase in the emerging-markets allocation, so emerging markets factor a lot more in our decision making than in the past. Second, over the last year or so we developed a Europe equity model that, along with our emerging-markets equity model, gives us a better sense of what returns we can expect from investing outside the United States.

To reduce stock exposure further, our next trigger point will be a function of how overall global equity markets perform. From current levels, assuming no change in fundamentals or our analytical inputs, if global equity markets were to rise another 5%–10% across the board, we may reduce equity risk from a half to a full notch, depending on the portfolio.

All-time stock market highs, coupled with your thoughts on deleveraging, make an argument that we’re due for a severe pullback in the equity markets, perhaps over a prolonged period of time. If there is a long, slow decline of 30%, how will the portfolios stand up?

It’s hard to give a precise answer to this question because the performance of our portfolios will be driven by a number of factors besides the assumed 30% decline in the U.S. stock market. To state the obvious, it will depend on the performance of all the asset classes and strategies that we have exposure to in our portfolios, and also the extent to which our actively managed funds add or detract performance relative to the market indexes. It will also be driven by the impact of any tactical asset allocation moves we may make during the period as the U.S. market is declining. And those tactical allocation decisions will be driven by our assessment of relative risks/returns across asset classes and a range of scenarios, and based on our view of the fundamentals and valuations.

But from a 36,000-foot view: Our more “risk tolerant” (equity-centric) balanced portfolios do have meaningful U.S. equity risk exposure, so on an absolute basis they would certainly take a hit from a 30% drop in U.S. stocks. But our most defensive balanced portfolio (20% stocks/80% bonds) has only 3.5% in U.S. stocks currently. So that portfolio should be well insulated from a sharp stock market decline.

At the same time, we have a meaningful tactical underweight to U.S. stocks across all of our balanced portfolios relative to their long-term strategic allocations. The underweight to stocks is in the range of nine to 11 percentage points, depending on the portfolio. And within our U.S. stock allocation we are also underweight to smaller-cap stocks, which we see as even more overvalued than larger-cap stocks and expect to have more downside risk in this type of scenario. So our tactical underweighting to U.S. stocks should certainly be a positive for our performance relative to our strategic allocations.

The magnitude of the benefit from our tactical underweight to U.S. stocks depends, of course, on the performance of the asset classes and funds where we are invested in place of that U.S. stock exposure. For the most part we are invested in funds and asset classes that we believe have less downside risk than U.S. stocks. So to give a simple stylized example, if U.S. stocks are down 30%, and we are underweight U.S. stocks by 10 percentage points, and the funds we are invested in for that 10% of the portfolio are down, say, 5% in aggregate, our tactical positioning would add 2.5 percentage points of relative performance. Again, this is a just a hypothetical example. But it’s not too far off from some of the severe stress-test 12-month scenarios we look at.

In our more risk-tolerant portfolio strategies, some of our U.S. stock underweight is in a slight tactical overweight to emerging-markets stocks. For those portfolios some of our relative performance in a sizable stock market decline will depend on the relative performance of U.S. versus emerging-markets stocks. To be conservative, or realistic, we don’t assume that emerging-markets stocks perform better than U.S. stocks in a prolonged market downturn, though that certainly could happen. But we do believe emerging-markets stocks should still outperform U.S. stocks across most scenarios over a longer five-year time frame.

…How would you hypothetically manage through such an environment?

As noted earlier, our results will be impacted by any tactical portfolio changes we might make during this period of market decline. We expect if there were such a large market drop, we’d finally be looking at pretty attractive, prospective five-year expected returns for U.S. stocks, so there is high probability we’d be incrementally increasing our exposure to U.S. stocks. Again, the timing and magnitude of our tactical move in U.S. stocks would depend on what was happening to other asset classes as well. But it is certainly possible we’d get back up to our strategic allocation to U.S. stocks, or ultimately even end up with an overweight position in U.S. stocks given a stock market decline of 30%.

What is your outlook on Japan now that they’ve announced an aggressive shift in monetary policy?

While Japanese stocks may continue to rise on the back of the recent announcement of more aggressive quantitative easing, we still can’t make a compelling long-term valuation case for a tactical position in Japanese equities after factoring in Japan’s relatively poor aggregate corporate profitability, corporate management (not shareholder-focused), economic and earnings growth, and public-debt dynamics. Japan’s profitability is about half or less than its developed, and even emerging-market, peers. So, we want to see a greater valuation discount than we have seen thus far before we consider a tactical allocation to Japan.

What happens in Europe if there is a bank run? How will it affect your five-year scenario analysis?

We haven’t explicitly modeled this scenario, though we can attempt to provide a general idea of what it may look like. It would surely impact our assessment of Europe. We believe a bank run in Europe would be a major short-term negative for European stocks, and it may lead one or more countries to exit the eurozone. Even if the eurozone holds together in its current form, earnings will likely be hit, valuations will compress, banks would need to be recapitalized, and we might see a spate of corporate bankruptcies and share dilutions, so there might be permanent capital losses for equity holders. In short, a full-blown depression in Europe could become a real risk, although it seems likely the European Central Bank would step in before Europe entered such a vicious negative spiral.

…Would it be reasonable, then, to think that you might initiate another fat pitch to Europe in such a scenario?

If this scenario plays out, we’d want a greater margin of safety before considering a tactical fat pitch in Europe. We may also lower our normalized cash earnings number for Europe to factor in depressionary conditions, meaning European equity prices would have to go down further than they did last June in order to make expected returns attractive.

…How would a European bank run affect domestic markets?

It is highly likely there will be a negative impact on U.S. stocks in this scenario. Many of the large U.S. companies derive a significant chunk of their

profits from Europe, so a depressed Europe will hurt U.S. companies’ profits in the short term. The dollar would likely appreciate, maybe sharply, versus the euro, which would also be a negative for U.S. companies with Europe-derived profits. Lastly, U.S. financial institutions may be forced to raise capital given any remaining linkages to European banks (although this risk is not as material as it was a few years ago, as the evolving European debt crisis has given many U.S. financial institutions time to manage the risks stemming from their exposure to Europe). Overall, it seems unlikely that a Europe bank run will cause a material reset to our long-term normalized U.S. earnings numbers, so this scenario might even offer us an opportunity to add to domestic equities if the U.S. stock market sold off materially in response to scary headlines from Europe.

The United States has been the strong horse during the global economic recovery. How long could this relative-performance streak extend and what would be the consequences to your portfolios, where you’re underweight U.S. and overweight foreign markets?

We can’t confidently say how long the U.S. relative-performance streak can extend. We don’t know how the market will perform in the short term as there are so many variables that can influence its direction. What we do have confidence in is assessing long-term fundamentals, and we have seen that the market tends to reflect those fundamentals over the long term.

One reason U.S. stocks have done well is due to historically high profit margins. However, profit margins have historically also shown a tendency to revert to the mean, and we don’t see anything to indicate this time would be any different. Even if mean reversion takes longer than we expect,

margins are unlikely to expand much from present levels (even the raging optimists would agree with us here), implying EPS (earnings per share) growth would mostly come in line with top line (i.e., revenue) growth, or nominal GDP growth, which is hard to come by these days. Assuming valuations don’t expand materially from current levels, stocks could generate returns in the mid- to high-single digits over the next five years, so this hypothetical scenario would fall somewhere between our most likely and our optimistic earnings scenarios, and we expect better returns from foreign markets in aggregate. Even if our optimistic earnings scenario for the United States plays out, the opportunity cost of underweighting U.S. stocks relative to international stocks is not likely to be high in our view. However, our portfolios will underperform if a bear-case scenario for foreign stocks plays out, maybe because of a crisis, while an optimistic scenario in the United States is playing out, which could happen but given the global linkages we consider this outcome highly unlikely over a period of five years.

Do you have enough exposure to emerging markets given the lack of opportunity in domestic markets?

Yes, we believe we do. As mentioned earlier, we increased our strategic allocation to emerging markets from around 5% to 20% of total equities in January 2012. That is largely a reflection of the longer-term opportunities we see in these countries.

As we noted earlier, emerging-markets equities are quite attractive relative to U.S. equities. As a result, most of our equity-risk underweighting at the portfolio level is coming primarily from U.S. equities and secondarily from developed international equities. So in that regard we are tactically overweight to emerging-markets equities relative to developed world equities in our more equity-centric models. Now, in absolute terms low double-digit potential returns for a risky asset class like emerging-markets equities are good but not great. So, balancing both relative- and absolute-return considerations we believe we are positioned appropriately with regard to emerging-markets equities.

In addition to emerging-markets equities, we consider our exposure to emerging-markets local currency bonds in our balanced portfolios as part of our overall emerging-markets exposure, so that needs to be kept in mind too.

Finally, we have to qualitatively factor in some risks that are unique to emerging markets. For example, we have written about the potential of a disorderly unwind of China’s infrastructure bubble as a significant risk for emerging markets. This risk is not yet explicitly factored into our return estimates, but we account for it qualitatively and in the sizing of our position.

With an overweight to emerging-markets equity, do you have any concern with regard to currency?

No, we are not concerned about taking on emerging-markets currency risk, and in fact we prefer it, as reflected in our active position in emerging-markets local-currency bonds where currency is a major driver of both risk and returns. We think over the long-term, emerging markets’ superior balance sheets and superior growth prospects will continue to be favorable for emerging-markets currencies and act as a tailwind. So exposure to emerging-markets currencies is something we want to have in our portfolios. We also recognize that appreciation in emerging-markets currencies (which is obviously beneficial to our emerging-markets local-currency bond allocation), could present a headwind to companies reliant on exports. However, to the extent the emerging markets’ currency appreciation is in line with company-level productivity gains, its impact on profits is neutralized. Companies more exposed to local demand factors will benefit from stronger currencies as local consumers’ purchasing power increases, which may increase demand for these companies’ products. So we expect that the exposure to emerging-markets currencies we are getting from emerging-markets equities will be a neutral to positive factor for our portfolios.

Most people seem to think rates will remain unchanged, or artificially suppressed by the Fed, through 2015. In your scenario analysis, what will be the catalyst for higher interest rates? Will this lead you to add floating-rate loans to your less conservative portfolios as a hedge?

Our five-year scenarios aren’t driven by our conviction in any particular catalyst or event leading to higher rates over that time frame. As we’ve discussed in prior commentaries, there could be any number of drivers of higher rates over the next five years—and the rate rise could be back-end loaded, i.e., not a smooth and gradual rise in rates, but a sharp rise at some point in the latter years of our time frame.

The drivers of rising rates could be positive, such as a return to more normal economic growth, falling unemployment, an unwinding of the extreme Fed monetary policy, and overall reduction in macro uncertainty and reduced risk aversion by investors. Or they could be negative drivers, such as increased market fears about the credit quality of the United States, accelerating inflation expectations, and/or a sharply depreciating U.S. dollar.

As part of our portfolio and risk management process, we also consider a 12-month stress-test scenario in which rates rise sharply. We are not predicting this will happen, and we agree with most people that it is unlikely at the moment given the weak global economy and central bank policies. But, we also know that we can’t confidently say it can’t happen. Markets are surprised all the time by unexpected events. That’s what moves market prices, when something happens that hasn’t already been discounted in current prices. So as part of our risk management we want to consider how our portfolio may be exposed to (or benefit from) such unexpected shocks or lower-probability events.

The last part of this question concerns our tactical position in floating-rate loans, which we currently hold in our more conservative portfolios.

We could very well add to the floating-rate positions, but have no immediate plans to do so. This is something we are continually thinking about and assessing in terms of the risk and return trade-offs relative to our other fixed-income options. In terms of the timing, if there is a sharp rise in interest rates, less-interest-rate sensitive asset classes, such as floating-rate loans, could get more expensive as investors flock to them. Our existing floating-rate positions would benefit from this, but at some point they would become relatively less attractive compared to other fixed-income sectors. This is why we have already taken significant steps in our balanced portfolios to own a range of bond funds that we believe will better navigate a rising-rate climate relative to core bonds.

While negative headlines have come out of California, we are comfortable with the state’s credit. California’s overall fiscal situation has been improving over the past few years and that continues, though select cities are likely to still remain under fiscal pressure. For example, recently the city of Stockton received a ruling from U.S. bankruptcy court saying the city is qualified to file for protection under Chapter 9 of the bankruptcy code. Stepping back from the Stockton case, we do not see this bankruptcy approval as a systemic risk for the broader state. In November of last year, California voters approved Proposition 30, which increases state sales-tax rates for the next four years and marginal income-tax rates for higher income taxpayers for the next seven years. These changes are expected to add somewhere in the magnitude of $6 billion to state coffers. As a result, earlier this year Standard & Poor’s upgraded the state’s credit rating from A- to A. So overall, we remain optimistic toward the California muni market. But as always, fundamental analysis is key and we continue to gain our California muni exposure through muni bond fund managers in whose credit research and risk management capabilities we have confidence.

Putting credit aside, we recently evaluated whether it makes sense to diversify our California-only exposure for California-based clients. Adding national exposure would provide us access to a wider opportunity set while providing some diversification should the California muni market get hit from headline risk. However, our analysis indicates that by diversifying nationally, we would be giving up approximately 30 basis points of relative performance on an after-tax basis. Given the low level of yields in the muni market, and our view of California fundamentals, we feel this opportunity cost is too high to merit the change.

It seems that stock market volatility has come down significantly recently. How does that affect your active managers’ ability to find good stock-picking opportunities?

While our managers have not specifically mentioned to us that the decline in market volatility has impacted their ability to find good stocks, many of them have noted that as the market moved higher, the opportunities became less attractive in general. And of course there is a relationship between the steadily rising market and the low volatility. So in that regard, the low volatility may be associated with a less-rich investment opportunity set for some of our managers. Many of our managers also note that, in general, it is often short-term stock price volatility that creates the great long-term investment opportunities, as investors may overreact to short-term earnings news or other events. So a low volatility environment, broadly speaking, might be seen as a less fertile environment for stock picking opportunities for active managers, and particularly value-oriented or contrarian managers.

On the other hand, correlations across stocks have also come down pretty sharply over the past year. And as we’ve talked about before, this should be viewed as a positive development for active stock pickers as it suggests stock prices are being driven less by big-picture macro factors (like the risk-on/risk-off paradigm where people are either buying into the market as a whole via index ETFs or getting out of stocks) and more by individual company- or industry-specific factors and bottom-up fundamentals.

It’s also interesting to note that, at least in recent years, stock market volatility and correlation have moved roughly together. That is, periods of high volatility have been associated with high stock correlations. And conversely, we’ve seen low volatility and declining correlations recently.

More broadly, as a contrary market indicator, low volatility (or a low VIX) has not always meant poor stock returns are on the horizon. History shows periods (e.g., mid-1990s and mid-2000s) where low volatility persisted at low levels for several years and stocks did well. But there are also more recent periods where low volatility was indeed a precursor of a stock market correction and a spike in volatility.

—Francis Financial, Inc. & Litman Gregory Research Team